Microservices is a popular and widespread architectural style for building non-trivial applications. They offer immense advantages but also some challenges and traps. Some obvious, some of a more insidious nature. In this brief article, I want to focus on how to integrate microservices.

This overview explains and compares common patterns for dealing with data in microservice architectures. I neither assume to be complete regarding approaches nor do I cover every pro and con of each pattern. As always, experience and context matter.

Four different parts focus on different patterns.

- Sharing a database

- Synchronous calls

- Replication

- Event-driven architectures

In the last article we discussed synchronous calls. The resulting challenges on a technological and organisational level led to surprising insights.

This article introduces replication as a pattern for data-integration in microservice landscapes. We will look at the basic concepts and especially at their use in hybrid landscapes. Landscapes, where we want to integrate pre-existing datastores with microservices.

Classical replication at 10 km

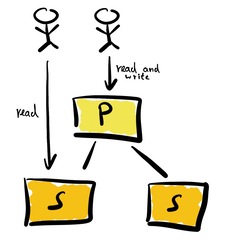

First of all, let’s discuss replication itself. We use replication to increase reliability, allow for fail-over and improve performance. The following sketch illustrates a very simplified view of replicating data.

One primary and two secondary instances of a database are set up for replication. Each change to the primary instance is also sent to the secondary instances. If the primary instance fails, an actor could switch to one of the secondary instances. The primary instance is the only one capable of processing any modifications. The primary instance handles all creation, deletion, or modification requests. The primary instance processes these requests. Then it forwards the changes to the secondary instances. This setup works best for read-mostly use cases, as data can be read from any instance.

This design looks trivial at first sight. But the implications warrant some discussion.

- How is consistency ensured?

- What happens if actors read from the secondary instances and the instance is not up to date?

- What happens if the network breaks between the instances?

- and and and.

We discuss these issues in detail in the following sections.

Replication in microservice landscapes

Let’s take a concrete example to drive the discussion. Suppose a bank wants to modernize its IT and move towards a microservice landscape. One large SQL database stores the financial transactions of customers. This database is of high value to the enterprise and is considered to be the Golden Source. This means that this database contains the “truth” about all data stored within. If the database says you transferred some money from A to B, then this is a fact.

The microservice could access the database directly, see the following illustration.

As we saw in part one, sharing a database in this way has its own downsides, such as:

- Classical databases often only scale vertically. There is an upper limit to the number of clients such a database can serve at the same time.

- The classical database may not be available 24/7. It might have some scheduled, regular downtime.

- More often than not, the data-model of the database does not fit the use-cases of the microservices.

- The ownership of the data may be unclear.

So, how does one get from the architecture above to something like the following?

This is where advanced replication tactics enter the scene. There are many ways to tackle this problem. We focus on Change-Data-Capture and complex transformation pipelines.

Change-Data-Capture

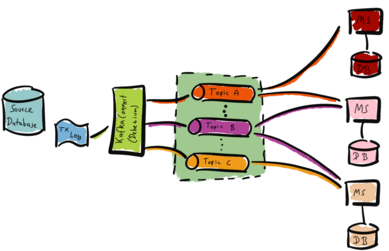

The Change-Data-Capture (CDC) framework hooks into a source database. The framework captures all changes to the data - hence the name. Afterwards, the CDC framework transforms and writes the data to a target database. One example technology for this use case is Kafka. The following illustration visualizes this approach.

We hook into our source database for example with Kafka Connect and Debezium. Debezium reads the database’s transaction log (TX Log). Debezium forwards changes to the transaction log to Kafka topics. The microservices (MS) consume the data from the topics and fill their databases (DB) as needed. We can optimize the microservice-databases for the respective use case. For example, one microservice might need a PostgreSQL whereas another needs a Redis.

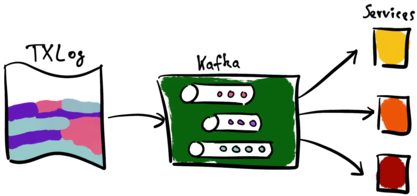

The initial load can take some time. The framework exports the complete source database. The consumer must manifest or reconstruct the destination databases. But once finished, later changes are fast and small. The next diagrams illustrate this.

The CDC pipeline (again, Kafka) processes all entries of the transaction log (TX Log). It stores each entry in Kafka-topics and forwards it to the receiving services. These services in turn manifest their local view of those entries.

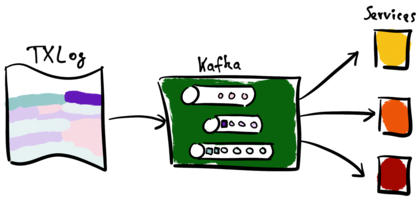

The services are operational after the initial run. The CDC pipeline processes only new entries to the transaction log. The next illustration shows this step.

The transaction log contains new entries. These new entries result in new Kafka events. Note that the top-most topic does not contain new events. Kafka forwards the new events of the bottom two topics to the services.

Creating such a streaming platform extends the scope of this article. We only scratched the surface and omitted many relevant details. This article describes the approach using Kafka tooling.

Complex transformation pipelines

We can also transform and enrich the data as part of the data replication process. Let’s use financial transactions as a trivial example again. The next illustration depicts such a pipeline.

The source database stores financial transactions. We use CDC to extract data from the source database and to push the data into raw databases (TX-DB). The raw databases contain copies of the original data.

In our example, some machine learning tool-set (ML-Magic) analyses the raw data. The result of the analysis is a categorization of the financial transaction. The ML-Magic combines the analysis and the financial transaction data. Finally, the ML-Magic stores this result in a separate enhanced business database. In the example, this is a MongoDB database.

Microservices use only the business databases. These are derived from the raw data and are optimized for specific use cases. The business database could for example be optimized and contain a denormalized view of the data. New business databases can be added as new use cases arise.

Implications

Change-data-capture and transformation pipelines are both valid approaches. Both help to move from existing system landscapes towards a more flexible architecture. We can adopt a microservice landscape without any modification to the existing assets. The microservices each end up with their optimized data-store. This decouples the development teams and increases agility.

However, introducing Kafka and similar frameworks increases the development complexity. Even so, this may be a valid investment. The resulting architecture may enable the business side to move and grow faster.

But nothing is a silver bullet. We identify at least the following questions that are worth further investigation:

- The Golden Source remains. What should happen if microservices create new data or change existing data?

- CDC and transformation pipelines take time. How should we deal with data in different states in different parts of our system?

- How can we ensure that data is only used by systems allowed to use said data?

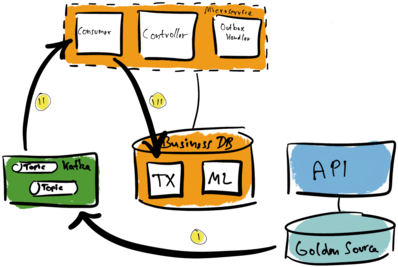

Again, let’s discuss a concrete example. We have talked about financial transactions. Our current system looks like illustrated by the following diagram.

We hook into the source database (Golden Source) again with Kafka Connect and Debezium (I). Kafka topics store transaction log entries as events. The microservice consumes the topics it needs (II). Afterwards, it manifests a local view in its local business database (III).

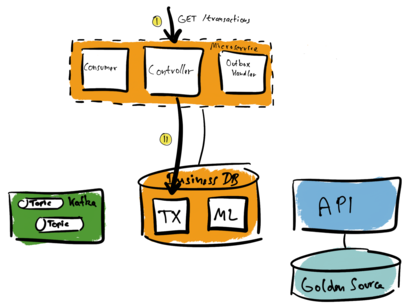

If we want to read financial transactions, we need to query the local business database. The microservice owns the business database. In the following illustration, a caller sends a GET request to the microservice (I). The microservice queries the optimized local database (II) and answers the GET request.

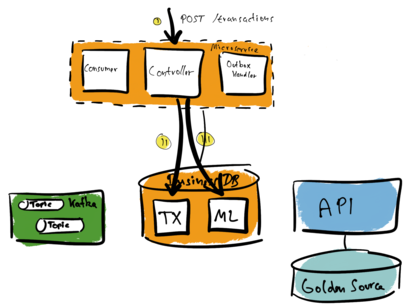

But what happens if a client asks the microservice to make a new transfer? A caller sends a POST request to the microservice. The microservice adds the new transaction to its local database. Remember that the Golden Source is the pre-existing source database. It contains the truth. Especially the truth about any financial transactions. So we need to send the information about the new transaction also to this database.

How do we approach this?

We could update the local database and then call the API to update the Golden Source. But what happens if the API call fails? Then we need to clean-up the local database and send the error also to the caller.

We could call the API first and only update the local database if the call was successful. Again, this is not as simple as it seems. The problem is the remote call to the API. There are error cases like e.g. timeouts, that leave us clueless. We do not know if the API call booked the transfer at all.

In the end, it doesn’t matter. We cannot span a transactional context across a HTTP API call and a local database in a meaningful way. Consider the documentation of the good-old HeuristicCommitException.

In a distributed environment communications failures can happen. If communication between the transaction manager and a recoverable resource is not possible for an extended period of time, the recoverable resource may decide to unilaterally commit or rollback changes done in the context of a transaction. Such a decision is called a heuristic decision. It is one of the worst errors that may happen in a transaction system, as it can lead to parts of the transaction being committed while other parts are rolled back, thus violating the atomicity property of transaction and possibly leading to data integrity corruption.

There is a pattern that can help us with this scenario: the outbox. We introduce a message log table (ML). A so-called outbox handler forwards all data of the message log to the Golden Source. See the following illustration.

Updating the message log and the transaction table (TX) happens as one transaction (II and III). Both tables are part of the same database, so a single local transaction is enough. The microservice can return the result to the caller and finish the request.

Now we get to the tricky part. Handling the message log. Often the API triggers some process side-effects besides updating the Golden Source. For example, calling out to other APIs or sending messages downstream.

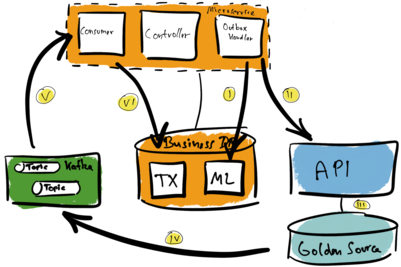

The following diagram explores the communication flow.

The Outbox Handler polls the message log table or subscribes to changes to it (I). It reads the data and calls the API (II). If calling the API was successful, then the handler marks the message log entry as done. Otherwise, the Outbox Handler retries the operation. If all fails, the handler marks the entry as not processable.

In such cases, other mitigation strategies come into place. But this is outside of our discussion.

Suppose the API call was successful. Next, among other things, the API call updates the Golden Source (III). This triggers the CDC pipeline. The CDC component captures the new data added to the Golden Source’s transaction log. Afterwards this data ends up in the Kafka topics (IV). The consuming microservice receives that data (V). Finally, the microservice updates the business database. The database now reflects the state of the Golden Source, too (VI).

We have omitted many technical details. Still, the complexity of this pattern should stand out. Many things could go wrong at any point. A solid solution must find mitigation strategies for each error case.

Even so, the eventual consistent character of this architecture does not go away. The new data stored in the business database does not reflect the Golden Source data right away. The time delay may or may not be an issue for the concrete use case. But we need to be aware of it and should analyse the impact of it.

The same holds for the topic of data governance. The patterns of this article lead to data replication, i.e. to storing the same data in many places. Depending on the regulatory requirements, we need to control which parts of the system landscape can use which data. This has to be set in place right from the beginning. Refactoring data governance controls into an existing landscape can be very challenging.

Last but not least, let’s not forget that CDC leads to technical events. Real domain events representing business-level processes are not captured.

Summary

All things considered, this can be a good option to grow from a static large datastore to a reactive and distributed multi-datastore landscape.

Moving towards modern architectures without any major refactoring of existing systems is possible. We can leverage and use so-called legacy systems without any direct extra cost of doing so.

We do not change existing systems. So we end up with the “old”, “legacy” system landscape, and the new microservice landscape. Complexity and cost increase. We need more engineers. We need more infrastructure. And so on.

But, we must not confuse this with event-sourcing or an event driven architecture. It can be the first step into those areas, but only the first. We are considering technical events a la “Row x in Table y has changed in values A, D, F”. This is different from saying “SEPA Transaction executed”. And we have to deal with eventual consistency. There is no way of avoiding this.

In conclusion, we need to check the advantages and implications of the approaches. There cannot be the best answer. We need to consider the concrete requirements and use cases. These determine if this approach is a good fit for our challenge and strategy.

Here are some references for more in-depth information on related topics:

- Change Data Capture Pipelines with Debezium and Kafka Streams

- No More Silos: How to Integrate Your Databases with Apache Kafka and CDC

- Reactive design patterns, Roland Kuhn et. al.

- Reliable Microservices Data Exchange With the Outbox Pattern

Outlook

The next and final installment of this series tackles event-sourcing and event-driven-architectures. Both powerful and related concepts. We will look at their implementation and advantages. But as always also at their implications on design and architecture.